| Date |

May 7, 2024

|

|---|---|

| Content Type |

User Story

|

| Author(s) | |

|

|

| Data Applications |

Ecosystem Monitoring

Water Quality

|

There are 890 freshwater bodies across Cape Cod, collectively referred to as ponds. These ponds are an indicator for groundwater quality for the peninsula, dubbed the “windows on our aquifer” by locals. Several towns and villages rely on Cape Cod’s groundwater aquifer as the primary source of drinking water treatment. Residents and tourists alike also enjoy recreational activities at the 96 ponds that are publicly accessible. Additionally, the Cape fosters ecosystems of plants and animals that rely on the freshwater bodies. As such, proper management and monitoring of the ponds are of great importance to the region.

Eagle Pond - Credit: Cape Cod Freshwater Initiative forum user annereynolds.

Cape Cod’s ponds have experienced variable water quality over the years due to water pollution inputs, including fecal bacteria, harmful cyanobacteria blooms fueled by nutrient runoff, emerging contaminants, and mercury pollution. A stakeholder engagement study in the Monomoy Lens of Cape Cod found that visitors are 1.8 times more likely to visit ponds that have rare or no bacterial issues, compared to ponds with recurring seasonal issues. When surveyed in 2021, around a third of the ponds had “unacceptable” water quality.

Monitoring of Cape Cod’s ponds is federally regulated through the Clean Water Act Sections 205, 208, and 303, and by The Massachusetts Public Waterfront Act and Wetlands Protection Act, Chapters 91 and 131, respectively. Regulations generally include managing water pollution and discharge, maintaining public access to the ponds, and conducting resource management planning. Each of these requires municipalities to conduct extensive monitoring of water quality. The Pond and Lake Stewardship Program (PALS), a volunteer-based program, helps coordinate monitoring efforts across Cape Cod-focused organizations.

According to Andrew Gottlieb, the Executive Director of Association to Preserve Cape Cod: “Satellite imagery provides us the ability to more intelligently deploy our resources going forward and to understand what types of [water quality] changes we may or may not be seeing based on the ability to actually turn back time and look.” While there is a significant amount of water clarity data available from historical and ongoing field monitoring programs, there are many ponds that are rarely or never monitored. Ponds can be difficult to access, and there are limited resources to support the necessary time and costs associated with frequent monitoring. Despite these challenges, routine large-scale monitoring of water clarity is needed to inform and implement effective pond management.

Satellite imagery has been established as an effective tool for providing frequent, large-scale observations of water clarity. On Cape Cod, satellite imagery complements traditional field-based measurements to improve spatial and temporal coverage of water clarity estimates while reducing costs and labor. A study led by CoastWatch scientists in partnership with local colleagues used satellite imagery from the joint USGS/NASA Landsat Program dating back to 1984, and the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite series dating back to 2015, allowing for both long-term retrospective and recent short-term analyses.

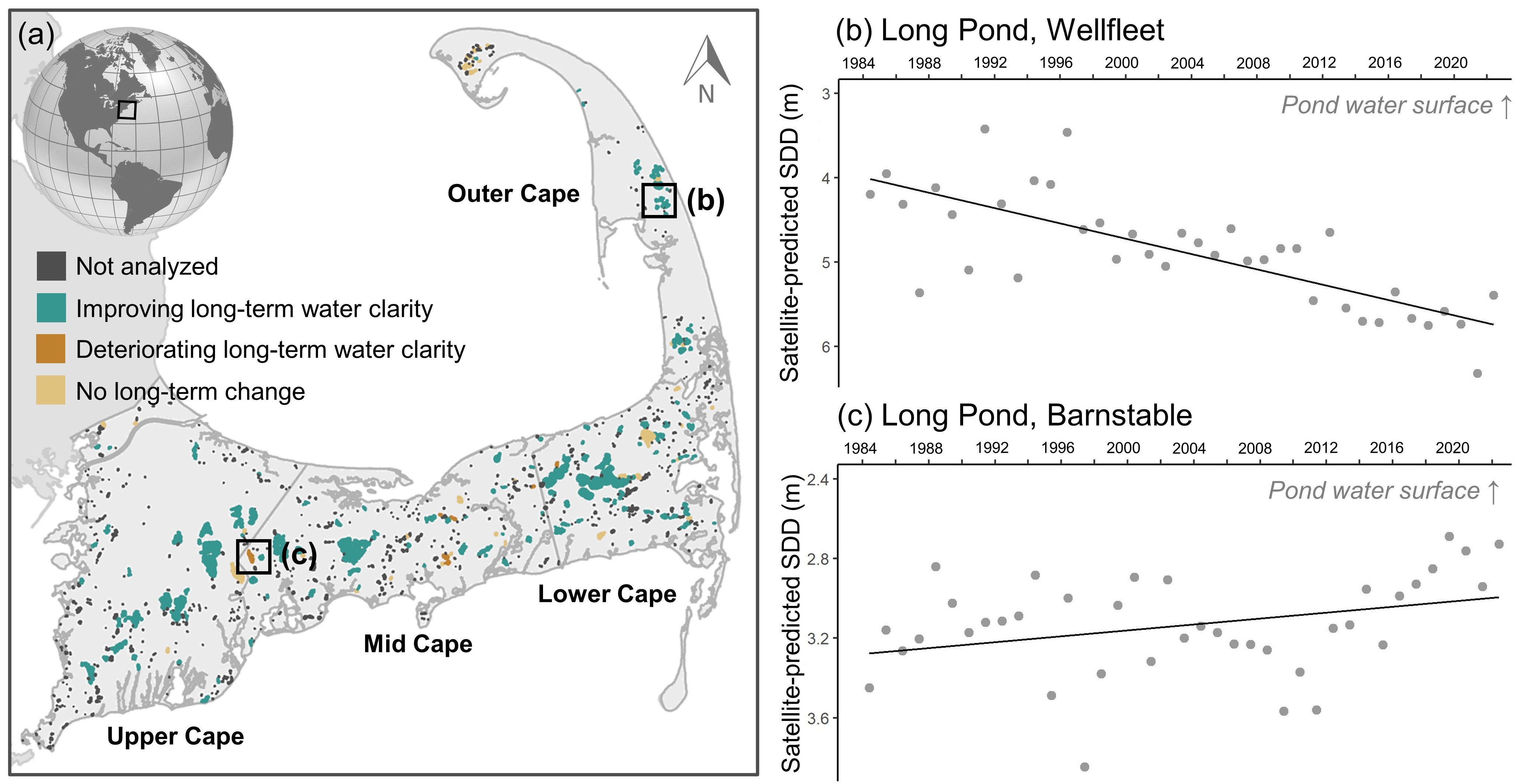

Water clarity was assessed for 193 ponds across Cape Cod, selected based on a minimum surface area of 1 hectare to accommodate the spatial resolution of the satellite sensors, and the availability of maximum pond depth data – an important variable in predicting water clarity. While these ponds constitute only 22% of the 883 ponds across the Cape, they represent over 85% of its freshwater surface area, providing the most spatially comprehensive assessment of Cape Cod ponds to date. Field observations collected intermittently across 154 ponds from 2001 to 2022 were compiled by the Cape Cod Commission and used to train a machine learning model to predict water clarity using satellite imagery. Statistical analyses indicated a “very strong” association between field-measured and satellite-predicted data, indicating satellite imagery was well-suited for predicting water clarity.

Cape Cod ponds, including those that were not analyzed in the current study (black), those analyzed that corresponded to field-measured Secchi disk depth (SDD; blue), and those analyzed without field-measured SDD (yellow), where SDD is a measure of water clarity. Ponds not analyzed were excluded either because they were less than 1 ha in surface area or because maximum pond depth data was not available. - Credit: Coffer, et al. (2024).

In 2022, water clarity across most of Cape Cod ponds was good, with median water clarity across the Cape’s 15 towns classified as either “suitable” or “eminently suitable” for recreational activities. Additionally, long-term retrospective changes in water clarity were assessed from 1984 to 2022, and recent short-term changes in water clarity were assessed between 2021 and 2022. Long-term change assessments provide baseline information and offer a range of historic water clarity conditions. Short-term change assessments benefit efficient resource prioritization; for example, ponds with deteriorating year-over-year water clarity may warrant additional field measurements the following monitoring season. Long-term retrospective analyses suggested that water clarity generally improved, with 81% of analyzed ponds showing a significant increase in water clarity over the past four decades. However, recent short-term analyses indicated year-over-year deterioration in water clarity for 50% of the ponds.

The study – published in the Journal of Environmental Management – defines a framework for monitoring and assessing change in water clarity using satellite imagery. This is important for local and regional management, and resource prioritization. Future efforts will focus on the following: increasing the number of observable ponds by including additional estimates of maximum pond depth; investigating drivers of water clarity, including nutrient concentrations, water temperature, and nearshore development; and exploring the feasibility of a similar machine learning approach to estimate chlorophyll a concentrations.

Study citation: Coffer, Megan M., Nezlin, Nikolay P., Bartlett, Nicole, Pasakarnis, Timothy, Lewis, Tara Nye, DiGiacomo, Paul M. (2024). Satellite imagery as a management tool for monitoring water clarity across freshwater ponds on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Journal of Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120334.